Demystifying Software Versioning

Commit hashes, build versions, backwards compatibility, forwards compatibility, package versions. Version 1, 2, 2.5, or 110319504efd76a2bbadd61af4c46562577bd15d.

The list goes on, and the jargon more vague as our industry matures. For many within software product development (both technical and non-technical) this can become overwhelming. In this post, I’ve attempted to make concise the most common forms of versioning in the hope that it will help cut through the jargon, and streamline understanding of versioning within software delivery.

Recently, I’ve written many posts that attempt to make technical concepts more accessible to the general public. They can all be found under the hash tag demystifying on this blog.

Versioning

When an artifact or asset is versioned, such as: code, a document, or even a material object; the state of it, at that particular time is persisted. These two attributes: the state of the artifact and the time of which it is captured means that every single version of an asset is unique.

In the context of digital assets, a version can be created on a very basic level by creating multiple copies of a file (for example: a word document), so that one can backtrack to a previous state.

Formatting

A version format is how to identify an asset’s state uniquely. At a preliminary level, a version can be an integer that increments by 1. For example: Version 1, Version 2, Version 3, so on and so forth. Or a decimal which incorporates a date. For example the Ubuntu versioning format: 4.10, 21.04, 21.10.

Different formats may represent different things, such as backwards

compatibility (whether the current version is compatible with a previous

version), the type of fix (patch or bug fix), or new features. For example if a

version goes from 1.2 to 2.0 it may mean a lack of backwards compatability.

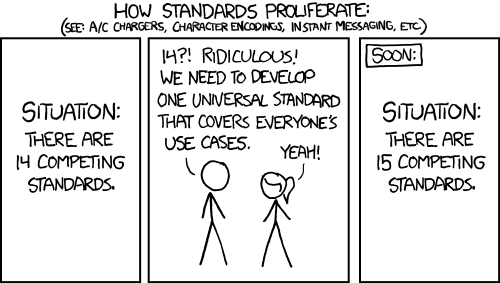

In an effort to make version formats uniform. Our industry has created multiple standards like: Semantic Versioning, known as SemVer and Calendar Versioning, known as CalVer. Ironically, a creation of a new standard almost never results in the uniformity of practice.

Code Version

Code versioning, at a basic level, is the state of code at a particular time. Prior to the introduction of modern source control tools, software engineers would make copies of code files for each version. With the introduction of these source control tools like SVN or GIT, the creation of different states at different times becomes automated. An engineer would modify code, and create a revision (often referred to as a commit). The tool then takes care of the different versions of the code and an engineer can easily navigate code at different versions.

Package Version

Code is compiled into either bytecode or binary code in order to be interpreted and executed by a computer’s CPU (Central Processing Unit). In software engineering workflows, it is important to run a series of black-box tests on a package (or build) version, not a version of the code in order to validate its correctness. As it is the package that is deployed into a target, and not the version of the code.

Whilst there is a degree of determinism when a specific code version is compiled into a package to be executed, there are situations which may affect the behaviour of the package itself. Although these situations are rare, the possibility of them occurring is present. Several variables may change a package’s (created from the same code) behaviour including (amongst others):

- Compiler version;

- Dynamic Configuration changes;

- Changes in external dependencies;

- The use of random numbers for certain algorithms within code (such as a cryptographic seed); and/or

- Other intermittent issues that may occur in the compilation phase.

With ephemeral computing on the rise, the issues above may occur more frequently, as such it’s important for any engineering team to pay close attention to package versions.

Release Version

The scenario described above of deploying packages instead of code, brought about the rise of the pattern of “build once, deploy everywhere”. What this means, is that the same package is deployed to the public as the one deployed into internal, controlled targets, such as a QA (Quality Assurance) environment. In order to be able to use the same package to deploy into different environments, certain variables need to be changed on deployment time (for example the URL of an email server). The state of these variables are often set by creating a ‘Release’. This is where a release version is often used.

Friendly Names

The two distinct attributes that define a version: the state of the artifact and the time of which that state is captured, means that versions are intrinsically unique. As such, versioning strategies and labels have to be unique as well. Often, unique hashes or decimals are used in order to capture that uniqueness, however, the disadvantage is that the identification of a specific version becomes difficult for humans to identify. Generally, humans find it easier to remember words and things, not decimals or random sequences of characters.

As such, software is often created with code names or human-friendly names. A great example of this is the Ubuntu operating system which uses a naming strategy focussed on animals. For example: Groovy Gorilla (which has the version 20.10) or Wily Werewolf (14.04).

Conclusion

In software, there are many layers of versioning involved depending on the stage of delivery, and it is important to ensure reliable and accurate traceability between these layers and their versions. For example: which release belongs to which package, and which package belongs to which source version. Versioning should be an exercise that is done through automated means and as part of an engineer’s usual workflow.

Organisationally, there must be a common understanding of versioning across technical and non-technical people in order to support a culture of collaboration that is focussed on knowing which versions contain which features, bugs, fixes, or experiments that will be presented to a product’s customers. This post aids in this common understanding by making versioning and jargon associated with it clearer and more accessible to a wider range of people.